Oldendorff Carriers is one of the world's largest dry bulk shipping companies, shipping and transhipping over to 300 million tons of bulk cargo every year and operating around 700 ships. Since 2018, Oldendorff vessels have been equipped with exhaust gas cleaning systems, commonly known as ‘scrubbers’.

These devices remove sulfur and particular matter from the exhaust gas stream in the funnel and enable the use of HFO while fully complying with the MARPOL Annex VI.

Since their implementation, concerns have been raised by several parties, mostly NGOs and environmental advocates, about the potential impact of scrubbers’ operation on marine life and water quality.

Although some research papers had been written on the topic, we realized that none drew clear conclusions and none were based on a full lifecycle assessment. There was a gap in the science that needed to be filled with high-quality data taken from independent in-situ testing.

It was therefore decided in July 2021 to run our own study to measure all air and water emissions generated by an Oldendorff vessel when operating a scrubber. This would enable us to compare these emissions with those resulting from other fuels used by the same vessel, and enabling an apples-to-apples comparison based on actual, onboard data.

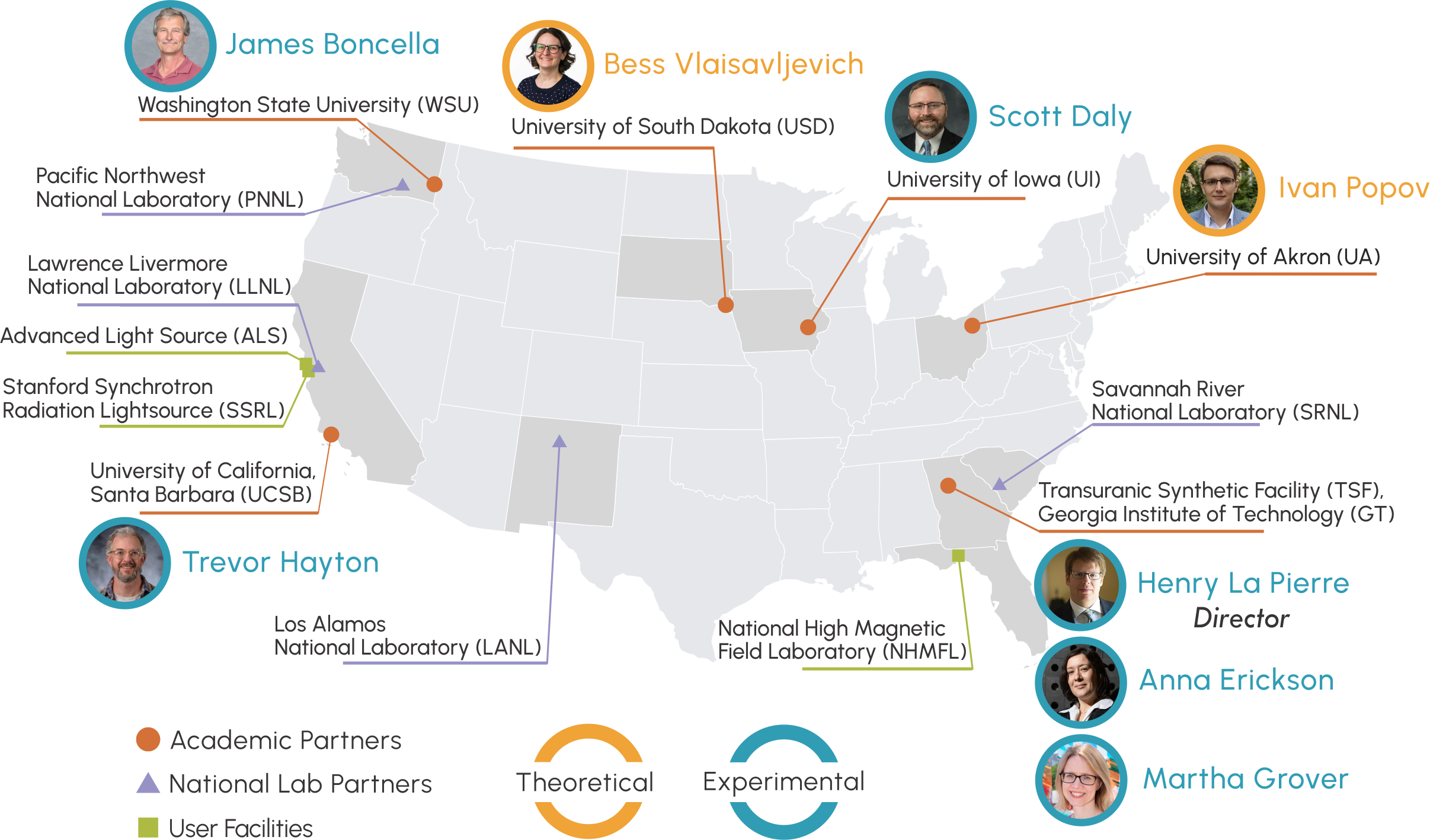

We were very lucky to get Dr. Patritsia Stathatou onboard for this project, currently with Research Faculty at the Renewable Bioproducts Institute at Georgia Tech, who at that time was a postdoctoral researcher at the MIT Center for Bits and Atoms (CBA).

Our “Hedwig Oldendorff” was selected as the guinea pig. Before any samples could be taken, several measuring instruments and sensors had to be installed onboard.

Additionally, we had to organize logistics and travel arrangements for Patritsia and for Ievgenii Petrunia, Senior Technical Manager from our Fleet Department who is collaborating with Patritsia on this project, so they could get onboard and perform the required research activities.

The entire preparation process spanned more than a year, given the multitude of factors that had to be taken into consideration, including:

– Ensuring that the monitoring equipment onboard was properly installed and fully operational.

– The vessel had to be at a suitable position to enable testing under different conditions and speeds without affecting our obligations towards our charterers. Also, it was important that Patritsia and Ievgenii could disembark from the vessel within a maximum of six days, together with several boxes of water and oil samples. The testing of these samples was time-critical, as they had to be sent to a laboratory in Greece for relevant analyses within a specific and narrow timeframe.

– Very low sulfur fuel oil (VLSFO) had to be bunkered at a convenient location, shortly before the commencement of the study, as its quality could deteriorate if left unused for a couple of weeks. In parallel, enough time had to be allowed for the timely availability of the laboratory test results. Before that, the crew had to prepare and clean one of the heavy fuel oil (HFO) tanks onboard.

– Research personnel had to obtain visas and needed to be available at short notice.

– Last but not least, there were a lot of auxiliary equipment and supplies which had to be shipped to the vessel on time.

Eventually, the chance to send Patritsia and Ievgenii came along. Patritsia has kindly shared her experience with us:

“After two years of preparing and organizing this study, here I am, finding myself in China for the very first time, standing aboard the huge bulk carrier vessel, “Hedwig Oldendorff”, with its awe-inspiring length overall of 299.95 meters! Hedwig was about to start her six-day journey from Taicang to the bustling port of Hong Kong with me onboard. During these six days my mission was to measure gas and particulate matter emissions both below and above the scrubber, at different engine modes and speeds, while the vessel was operating with HFO, and at the same time collect and prepare seawater and wash water samples from the scrubber operation. I also had to measure similar emissions under the same engine modes, while the vessel was burning marine gas oil (MGO) and VLSFO and collect samples for subsequent analysis from all the fuels, lubricants and cylinder oils used during the trip, to enable the renowned apples-to-apples comparison mentioned above.

I was so excited at the beginning! We have spent two whole years organizing this study and coordinating all the different components involved to make it happen, including identifying a suitable vessel, sourcing, shipping, and installing onboard the proper equipment, arranging a voyage of specific duration and conditions, synchronizing people’s schedules, and much more. The prospect of embarking on this thrilling adventure seemed both intriguing and exhilarating in theory. I had convinced myself that I knew exactly what lay ahead, confident in my understanding of the tasks that awaited me. However, when reality kicked in, my initial enthusiasm swiftly transformed into daunting fear. As I navigated through the enormous vessel, enveloped in a world of massive roaring engines and intricate machinery, I started being overwhelmed by the complexity and scale of the operation. As I beheld the towering 20-meter vertical ladder, a crucial component of my mission to ascend and descend in order to reach the “above the scrubber” sampling point and collect data under various conditions, I felt a wave of panic washing over me. The scorching heat, exceeding a blistering 45°C, made me sweat profusely, with my protective uniform and gear adding to my discomfort. The deafening roar of the engines filled the air, further amplifying my unease. Moreover, the vessel’s constant swaying, as it gracefully rode the turbulent waves, was a detail that had completely eluded my imagination until that very moment. It was in that moment of intense apprehension that I realized the harsh truth: I was utterly ignorant of the true implications behind the phrases “measuring emissions onboard” and “collecting our own, actual data”.

Thankfully, five extraordinary individuals emerged like superheroes, summoned to alleviate my distress: Lengenii Petrunia, Senior Technical Manager at Oldendorff whose expertise was invaluable; Konfederatov Evgeni, the Master, and the core technical team of the vessel whose support and contributions were priceless: Liashko Igor, the Chief Officer, Omelyanenko Ivan, the Chief Engineer, and Zaytsev Serhiy, the Second Engineer.

It was through the tremendous support of this extraordinary team aboard, that my fear and discomfort gradually dissipated. Their wisdom, respect, and expertise helped me not only to successfully perform the required tests and collect the samples needed, but also to embrace the entire experience with joy. Surpassing my initial trepidation, I conquered my fears of climbing ladders, acclimated myself to the loud sounds of roaring engines, and grew accustomed to the high temperatures. I meticulously set up my own floating laboratory, where I enjoyed preparing and storing my water samples, and begun to like working at the sweating conditions close to the engine and the funnel. After the day’s obligations were fulfilled, we continued our scientific endeavors well into the night. Together, under the dim glow of the vessel’s lights, we toiled tirelessly, undeterred by the hardships that beset us. Though weariness occasionally led to inadvertent errors and moments of frustration, the satisfaction of pushing past our limits and advancing our understanding propelled us forward. As the days unfolded, Hedwig, transformed into a place I could call home.

Upon our arrival at Hong Kong, I felt a mixture of satisfaction and pride for our collective efforts, accompanied by a subtle tinge of sadness that our journey had come to an end.

Looking back, I am immensely grateful for this transformative experience that pushed me beyond my comfort zone and allowed me to witness first-hand the intricacies of measuring onboard emissions and collecting actual data. This voyage was not simply a physical journey across the sea nor just another field trip for me; it symbolizes a remarkable chapter in my scientific endeavors, further shaping me as a researcher. I am looking forward to analyzing the results and sharing the outcomes of this unforgettable journey. Thank you Oldendorff!”

While we are now waiting for the results of our study, we would like to thank everyone involved.

The whole project really became a team exercise and without the help of our various colleagues from departments including Bunker Desk, Procurement, Chartering, Fleet, Crewing, IT, Ops and of course our crew onboard nothing would have been achieved.