Dehydration Alters Human Brain Shape and Activity, Slackens Task Performance

Aug 23, 2018 — Atlanta, GA

Illustration for dehydration fMRI study. Free sources: Getdrawings.com and Remi Yuan on Unsplash

When dehydration strikes, part of the brain can swell, neural signaling can intensify, and doing monotonous tasks can get harder.

With the help of brain scans and a simple, repetitive task to test responsiveness, exercise physiologists at the Georgia Institute of Technology studied volunteer subjects who sweated a lot and did not hydrate. The fluid loss led most of the subjects to make more goofs on the task, and areas of participants’ brains showed conspicuous changes.

The researchers also found that even without dehydration, exertion and heat put a dent in test subjects’ performance, but water loss made the dent about twice as deep.

“We wanted to tease out whether exercise and heat stress alone have an impact on your cognitive function and study the effect of dehydration on top of that,” said Mindy Millard-Stafford, the study’s principal investigator and a professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Biological Sciences. “We found a two-step decline.”

Heat, strain, accident

The researchers hope that someday this kind of research will offer insights into how increased cognitive slipups in hot settings with strenuous labor and poor hydration may endanger occupational safety, especially around heavy machines or military hardware. The fuzzed cognition could also contribute to reduced performance in competitive sports.

“When I was just getting interested in this subject, my brother was doing an internship at a steel plant, where I visited him, and it was extremely hot,” said the study’s first author Matt Wittbrodt, a former graduate research assistant at Georgia Tech. “In addition, everyone had on layers of protective clothing. We want to figure out if we can help prevent accidents in those environments.”

Millard-Stafford and Wittbrodt, who is now a postdoctoral researcher at Emory University, published their study on Thursday, August 23, in the journal Physiological Reports. Their research was partly funded by The American College of Sports Medicine Foundation.

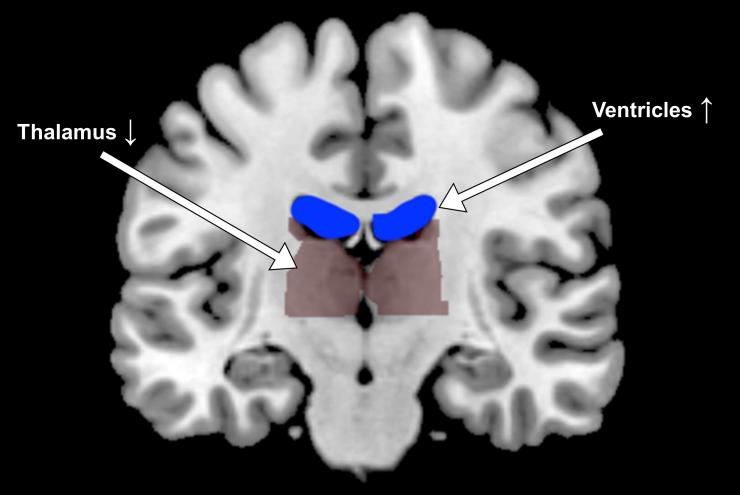

Brain ventricles expand

In the experiments, when participants exercised, sweated and drank water, fluid-filled spaces called ventricles in the center of their brains contracted. But with exertion plus dehydration, the ventricles did the opposite; they expanded.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) revealed the differences. Oddly, the ventricle expansion in dehydrated test subjects may not have had much to do with their deeper slumps in task performance.

“The structural changes were remarkably consistent across individuals,” said Millard-Stafford a past president of The American College of Sports Medicine. “But performance differences in the tasks could not be explained by changes in the size of those brain areas.”

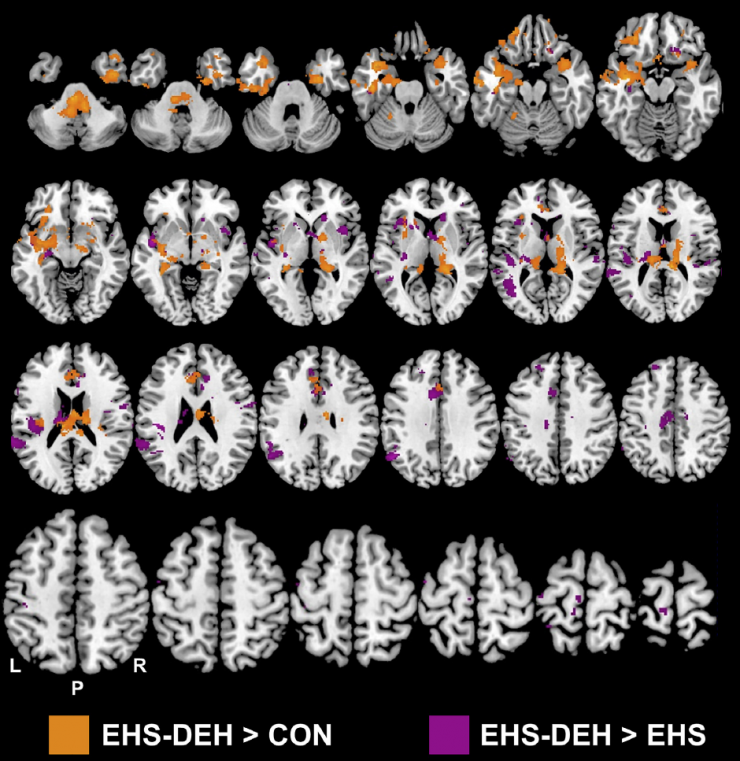

Changes in neural firing patterns showed up during dehydration, too.

“The areas in the brain required for doing the task appeared to activate more intensely than before, and also, areas lit up that were not necessarily involved in completing the task,” Wittbrodt said. “We think the latter may be in response to the physiological state: the body signaling, ‘I’m dehydrated’.”

Mind-numbing task

The task the subjects completed was mindless and repetitive.

For 20 straight minutes, they were expected to punch a button every time a yellow square appeared on a monitor. Sometimes the square appeared in a regular pattern, and sometimes it appeared randomly. The task was dull for a reason.

“It helped us to avoid the cognitive complexity behind elaborate tasks and strip cognition down to simple motor output,” Wittbrodt said. “It was designed to hit essential neural processing one would use to make straightforward, repetitive movements.”

Past studies have indicated that this kind of task reflects the neural processing involved in real-life motor functioning, especially in the repetition common in manual labor or military exercises. Such monotony can foster attention lapses that heat, strain, and fluid loss may exacerbate.

Sweating for science

Thirteen volunteers performed the task on three separate occasions:

- Once after just relaxing and staying hydrated.

- Once after extended heat, exertion, and sweat but with drinking water during exercise.

- And once with heat, exertion, and sweat but without drinking water.

Even after just relaxing, task performance gradually slipped as the 20 minutes crept by. But under the subsequent stressors, average overall performance ratcheted down. A few of the volunteers did perform the task stalwartly under all imposed conditions.

The subjects completed the task in air-conditioned rooms and after a break from strenuous activity. In a real-world scenario, in which heat and toil are unrelenting, performance may collapse even further.

Overhydration also bad

Going forward, the researchers would like to know if hydrating with electrolyte drinks might mitigate performance slumps even better than water did.

“Blood plasma gets diluted with water replacement alone,” Millard-Stafford said. “If blood sodium -- plain old salt -- drops too much while water in the blood increases too much, that’s dangerous. It’s a condition known as water intoxication or hyponatremia.”

Ultra-endurance athletes who end up in the medical tent are sometimes suffering from dehydration but also sometimes from water intoxication. Just the right balance of water seems to be important for the brain.

Like this article? Subscribe to our email newsletter

Also READ: As We Get Parched, Cognition Can Sputter

Georgia Tech’s Michael Sawka and Lewis Wheaton, and J. C. Mizelle of East Carolina University contributed to this study. Research was partly funded by The American College of Sports Medicine Foundation’s C. V. Gisolfi Doctoral Student Research Grant. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The American College of Sports Medicine.

Research News

Georgia Institute of Technology

177 North Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0181 USA

Media relations assistance: Ben Brumfield (404) 660-1408, ben.brumfield@comm.gatech.edu

Writer: Ben Brumfield

A research scientist withdraws sweat from a pouch on the back of a volunteer. Sweat is analyzed for electrolyte concentration among other biochemicals in Mindy Millard-Stafford's exercise physiology lab in Georgia Tech's School of Biological Sciences. Credit: Georgia Tech / Christopher Moore

fMRI image of a test subject's brain reveals expanded ventricles and a more compact thalamus. Credit: Georgia Tech / Millard-Stafford / Wittbrodt

A research scientist withdraws sweat from a pouch on the back of a volunteer. Sweat is analyzed for electrolyte concentration among other biochemicals in Mindy Millard-Stafford's exercise physiology lab in Georgia Tech's School of Biological Sciences. This photo is not connected with any particular study. Credit: Georgia Tech / Christopher Moore

A little bag collects sweat from the backs of subjects who participate in studies involving fluid loss and its possible consequences. This photo is not connected with a particular study. Credit: Georgia Tech / Christopher Moore

Professor Mindy Millard-Stafford researches in exercise physiology, including studies on how dehydration and exertion can reduce physical and cognitive performance. In the background, a volunteer lies on a device that measures body composition (l.) and another volunteer sweats out fluids under exertion in a heated chamber (r.). Millard-Stafford is a past president of the American College of Sports Medicine. Credit: Georgia Tech / Christopher Moore

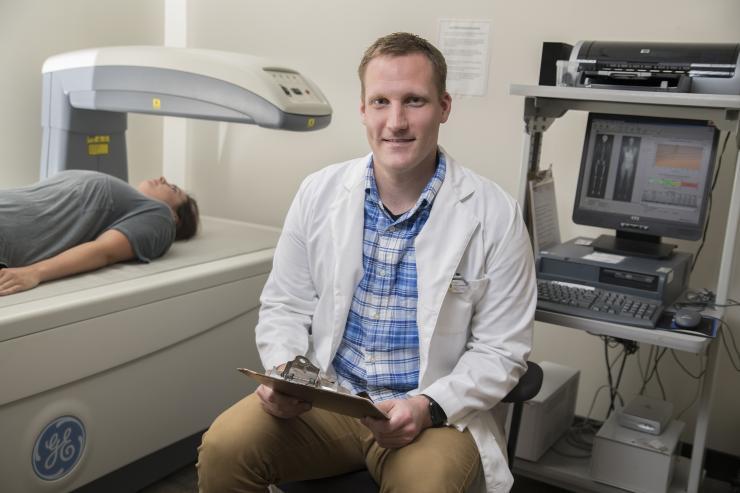

Matt Wittbrodt sits at a device that measures body composition. He is keenly interested in workplace accident risk factors possibly produced by dehydration and exertion and the ensuing decline in physical and cognitive abilities. Wittbrodt received his doctoral degree at Georgia Tech and is a postdoctoral research assistant at Emory University. Credit: Georgia Tech / Christopher Moore

fMRI of brain activity of dehydrated test persons. Orange represents the rise in activity over participants who experienced no exertion and no heat stress, but who hydrated. Purple is the rise in activity above test persons who experienced the same stressors as dehydrated test persons but who hydrated. Credit: Georgia Tech / CABI