The Electric Sands of Titan

Mar 27, 2017 — Atlanta, GA

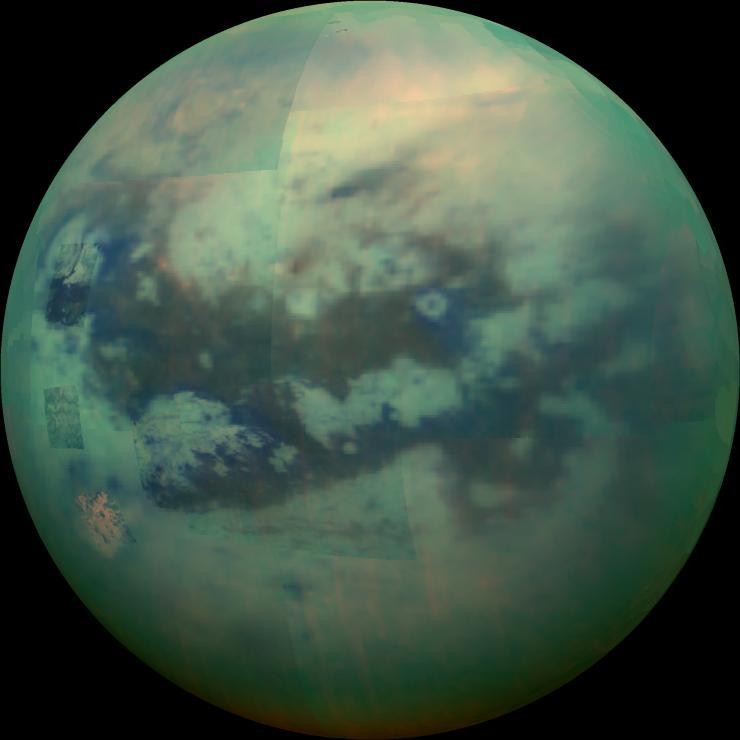

This composite image shows an infrared view of Saturn's moon Titan from NASA's Cassini spacecraft, acquired during the mission's "T-114" flyby on Nov. 13, 2015. Courtesy: NASA/JPL

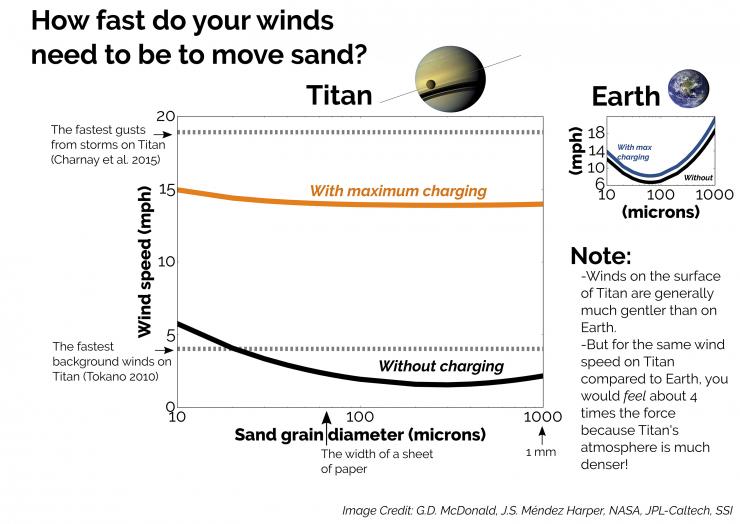

Experiments led by researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology suggest the particles that cover the surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, are “electrically charged.” When the wind blows hard enough (approximately 15 mph), Titan’s non-silicate granules get kicked up and start to hop in a motion referred to as saltation. As they collide, they become frictionally charged, like a balloon rubbing against your hair, and clump together in a way not observed for sand dune grains on Earth — they become resistant to further motion. They maintain that charge for days or months at a time and attach to other hydrocarbon substances, much like packing peanuts used in shipping boxes here on Earth.

The findings have just been published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

“If you grabbed piles of grains and built a sand castle on Titan, it would perhaps stay together for weeks due to their electrostatic properties,” said Josef Dufek, the Georgia Tech professor who co-led the study. “Any spacecraft that lands in regions of granular material on Titan is going to have a tough time staying clean. Think of putting a cat in a box of packing peanuts.”

The electrification findings may help explain an odd phenomenon. Prevailing winds on Titan blow from east to west across the moon’s surface, but sandy dunes nearly 300 feet tall seem to form in the opposite direction.

“These electrostatic forces increase frictional thresholds,” said Josh Méndez Harper, a Georgia Tech geophysics and electrical engineering doctoral student who is the paper’s lead author. “This makes the grains so sticky and cohesive that only heavy winds can move them. The prevailing winds aren’t strong enough to shape the dunes.”

To test particle flow under Titan-like conditions, the researchers built a small experiment in a modified pressure vessel in their Georgia Tech lab. They inserted grains of naphthalene and biphenyl — two toxic, carbon and hydrogen bearing compounds believed to exist on Titan’s surface — into a small cylinder. Then they rotated the tube for 20 minutes in a dry, pure nitrogen environment (Titan’s atmosphere is composed of 98 percent nitrogen). Afterwards, they measured the electric properties of each grain as it tumbled out of the tube.

“All of the particles charged well, and about 2 to 5 percent didn’t come out of the tumbler,” said Méndez Harper. “They clung to the inside and stuck together. When we did the same experiment with sand and volcanic ash using Earth-like conditions, all of it came out. Nothing stuck.”

Earth sand does pick up electrical charge when it’s moved, but the charges are smaller and dissipate quickly. That’s one reason why you need water to keep sand together when building a sand castle. Not so with Titan.

“These non-silicate, granular materials can hold their electrostatic charges for days, weeks or months at a time under low-gravity conditions,” said George McDonald, a graduate student in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences who also co-authored the paper.

Visually, Titan is the object in the solar system most like Earth. Data gathered from multiple flybys by Cassini since 2005 have revealed large liquid lakes at the poles, as well as mountains, rivers and potentially volcanoes. However, instead of water-filled oceans and seas, they’re composed of methane and ethane and are replenished by precipitation from hydrocarbon-filled clouds. Titan’s surface pressure is a bit higher than our planet — standing on the moon would feel similar to standing 15 feet underwater here on Earth.

“Titan’s extreme physical environment requires scientists to think differently about what we’ve learned of Earth’s granular dynamics,” said Dufek. “Landforms are influenced by forces that aren’t intuitive to us because those forces aren’t so important on Earth. Titan is a strange, electrostatically sticky world.”

Researchers from the Jet Propulsion Lab, University of Tennessee-Knoxville and Cornell University also co-authored the paper, which is titled “Electrification of Sand on Titan and its Influence on Sediment Transport.”

The study is partially supported by the National Science Foundation (EAR-1150794). Méndez Harper held a National Science Foundation graduate fellowship while conducting the study. McDonald has a National Defense Science and Engineering Graduate Fellowship. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors.

An artist's rendering of the surface of Titan, a moon of Saturn. Courtesy: iPhoto Stock, manjik.

Jason Maderer

National Media Relations

maderer@gatech.edu

404-660-2926