Freeing a Scientific Mind to Envision Big Research: Packard Fellowship to Will Ratcliff

Oct 14, 2016 — Atlanta, GA

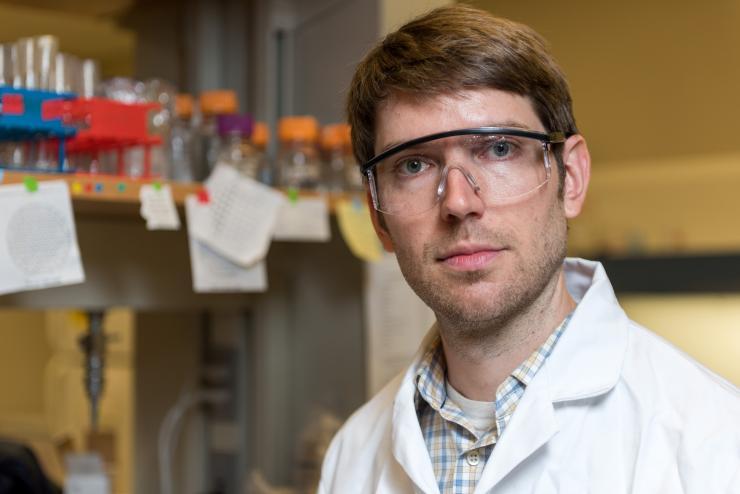

Will Ratcliff, an assistant professor in Georgia Tech's School of Biology, has been named to Popular Science's annual list of up-and-coming scientists, "The Brilliant 10."

Credit: Rob Felt

A vision recently came to researcher Will Ratcliff about the scientific legacy he’d like to look back on 30 years from now.

The moment of clarity was fueled by an award from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, which this week named Ratcliff a Packard Fellow for 2016. The prestigious fellowship has freed the evolutionary biologist’s mind to think beyond the previous horizons of his lab’s experimental goals.

Packard formally announced on Friday, October 14, that the annual fellowship was being awarded to 18 scientists nationwide. They will receive $875,000 each, paid out over a five-year period.

Ratcliff, who studies the evolution of single-cell organisms into multicellular groups at the Georgia Institute of Technology, found out he was one of the recipients a few days prior. And when he did, it sent his head reeling.

“The first night after I heard about it, I had these waves of thoughts like, ‘Hey, we could do this cool experiment!’” he said. “Then I’d go to bed and another one would jolt me awake, ‘Woah, and we could do this!’”

Fast-forward movie of life

Since then, a legacy goal has crystalized. “I want us to rewind the tape of life and watch it on fast-forward,” he said.

“I want to see how unicellular organisms evolve into bona fide multicellular organisms with robust division of labor, and multiple cell types. I want to see how development evolves from scratch,” said the assistant professor at Georgia Tech’s School of Biological Sciences.

Ratcliff has gained notoriety among biologists for producing conditions that have accelerated the evolution of yeast and algae cells from single cells into cell clusters that then grow in complexity and begin to specialize in cell function. One of his signature achievements is yeast cell groups called “snowflakes.”

In August, two months before the Packard announcement, the magazine Popular Science recognized Ratcliff in its annual list “The Brilliant 10,” which applauds a select group of up-and-coming scientists and engineers.

PopSci cited his work demonstrating how an evolutionary leap may have occurred that was key to the advent of plants and animals, but also arduous, since single cells had to forfeit much of their own fitness for the greater good of creating viable cell groups.

Evolutionary long game

Ratcliff thinks he may be able to shepherd a recapitulation of the evolutionary path that led to first complex beings within his lifetime by hyper-accelerating natural selection in the lab. And he believes the accomplishment would be valuable to science for a long time to come.

“We’ve never actually seen that process in real time,” Ratcliff said. “I want to put that movie of the tape of life on fast-forward in my laboratory to be able to understand the general rules that govern this evolutionary process. It would have profound implications of how complex life arises not just on Earth, but also elsewhere in the universe.”

Ratcliff says the Packard Fellowship will allow him to take the long view, and not only due to the award’s ampleness. “It’s very flexible in that they want you to be creative and feel free to pursue the research you find most exciting.”

Unlike most grants, this one’s not tied to specific research milestones.

“It’s designed to nurture you,” Ratcliff said. “They’re investing in the researcher, and as a result, I’m stepping back and taking stock of my research thinking in a way I never have before,” he said.

(READ: Georgia Tech's proud Packard Fellows through the years.)

Legacy research in future science

Ratcliff sees the fellowship as an opportunity to make an impactful contribution to evolutionary science, and has been inspired by the work of biologist Rich Lenski at Michigan State University.

Lenski has run a 28-year experiment viewed as classic in the field, evolving of E. coli bacteria in the lab for nearly 60,000 generations. The work has been an endless source of information and created a continuing legacy.

“One of the great things about experimental evolution is that you can create a living record of the entire experiment by live-archiving your populations in the freezer at regular intervals,” Ratcliff said. As decades pass, scientific and technological advances come along and allow researchers to exponentially boost the usefulness of that archive.

“In Lenksi’s experiment, for example, the recent revolution in genome sequencing means that they can examine the evolutionary dynamics of his entire experiment in ways they never would have expected,” Ratcliff said.

Ratcliff envisions using some of the Packard funding to establish evolutionary lines that he would continue throughout his career. “Hopefully for 20 or 30 years,” he said. “I’d love to take these simple multicellular things we have already and push them to see how complex we can actually get them.”

He would like to end up with a library of simple multicellular beings across multiple evolutionary phases.

Georgia Tech collaboration

But before he lays down details, Ratcliff wants to consult with his collaborators, particularly Georgia Tech physicist Peter Yunker. He’s been helping Ratcliff solve problems that organisms encounter as they become more complex.

“We’re looking at the materials properties of our (yeast) snowflakes,” Ratcliff said. “Evolving novel physical properties – bodies with specific functionality – is an often overlooked but major challenge facing nascent multicellular critters.”

Working with scientists from a different discipline has changed Ratcliff’s perspective by creating thought synergies, a legendary Georgia Tech strength. “The level of collaboration here is really unreal, actually,” Ratcliff said.

“From the president through the ranks, there is an ethos of collaboration,” he said. “That helps the science be better in the long term.”

A rare honor shared

A Packard Fellowship is a rare honor that starts with the foundation narrowing down to 50 the number of universities prompted to provide applicants. The universities are then instructed to nominate two scientists each, who write a two-page research proposal describing their future work.

“My faculty advisor told me, ‘This may be the most important two pages of your life,’” Ratcliff said. “I took that to heart and spent close to a month only writing the proposal.”

And he reached out to colleagues for help.

“I’m pretty confident that I wouldn’t have gotten it, if we didn’t have so many smart faculty here who are so eager to collaborate. I got feedback from about a dozen colleagues in the School, and that made the proposal stronger.”

Disclaimer: Any opinions, findings and conclustions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and/or researcher(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of any sponsoring agencies.

Yeast clumping together as a snowflake may represent how single-cell organisms took their first steps toward becoming multicellular beings then eventually plants and animals.

Credit: Will Ratcliff

William Ratcliff is enjoying a moment in the spotlight, after the magazine Popular Science put him on its 2016 roster of up-and-coming researchers, "The Brilliant 10," for his work illuminating a mystery of evolution.

Credit: Rob Felt

Writer and contact: Ben Brumfield

Research News

(404) 660-1408