Georgia Tech Faculty Win Research Awards to Advance Concentrated Solar Power

Jun 13, 2018 — Atlanta, GA

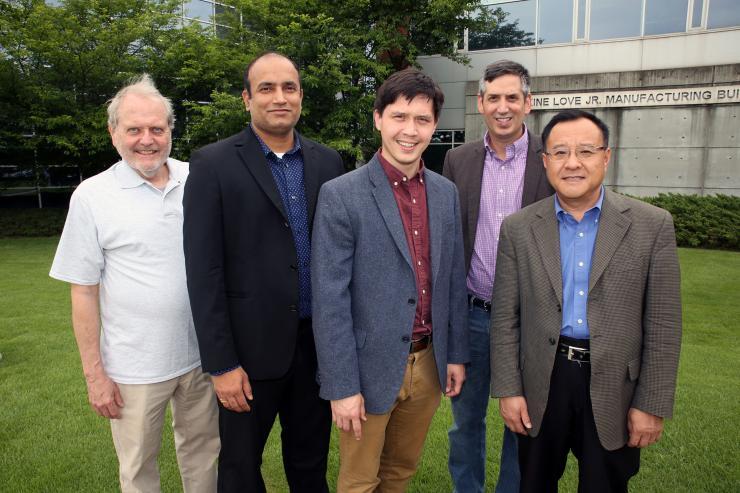

Georgia Tech is part of a new U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) initiative to develop the next generation of concentrated solar power (CSP). Shown (l-r) are Researchers Sheldon Jeter, Devesh Ranjan, Shannon Yee, Peter Loutzenhiser and Zhuomin Zhang. (Credit: Candler Hobbs, Georgia Tech)

Georgia Institute of Technology researchers are part of a new U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) initiative to develop the next generation of concentrated solar power (CSP), a technology that uses heat from the sun to turn power-generating turbines. CSP is an alternative to the better known photovoltaic technology, which produces electricity directly from sunlight.

Six Georgia Tech researchers will receive a portion of a $72 million DOE investment that will ultimately lead to construction and demonstration of an operating Generation 3 CSP facility. The Georgia Tech researchers will collect information on the thermophysical properties of molten salts used in concentrated solar facilities and study particle flows and heat transfer that may be part of thermal storage applications.

“Concentrated solar power is another option that allows us to generate electricity from sunlight,” said Shannon Yee, assistant professor in Georgia Tech’s George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and one of the award recipients. “Concentrated solar allows storage of the sun’s heat, so we can generate electricity even when the sun isn’t shining – at night, for example.”

Concentrated solar facilities use mirrors to concentrate sunlight that is then captured by solar receivers installed at the top of towers. Some existing installations use the heat to generate steam, which then drives a turbine to produce electric power. Engineers want to operate the facilities at higher temperatures – 700 degrees Celsius or above – to more effectively use the concentrated sunlight from fields of mirrors (i.e., heliostat fields) that deliver more concentrated sunlight to solar receivers than the widely used parabolic troughs.

“We have to move to higher and higher temperatures, which means we have to use materials that are more and more exotic,” said Yee, whose research team will receive a total of about $2 million during the five-year program. “We really don’t have the information we need about the thermophysical properties of these materials. Our goal will be to learn more about these materials, and to disseminate that information to the organizations that will be designing the new facility.”

An alternative to using molten salts is to use solid particle flows as a thermal energy carrier and storage medium to transfer thermal energy from the receiver to a working fluid to produce electricity. Understanding these materials will be the work of Associate Professors Peter Loutzenhiser and Devesh Ranjan, and Professor Zhuomin Zhang, all faculty members in the Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering.

“We will be working together to characterize flow and model the heat transfer for different particles under different conditions as they are applied to CSP applications,” said Loutzenhiser, whose team will receive $1.4 million from the DOE over three years. “The end goal will be supporting the use of particles as solar energy storage and carrier media to provide on-demand electricity derived from supercritical CO2 and/or Air Brayton cycles. Solid particles are advantageous because they have high energy densities and can operate to higher temperatures without much degradation compared to molten salts.”

Ranjan compared the particle flow to that of volcanic lava. “The particles can absorb a lot of heat and allow us to move the thermal energy,” he said. “We will be looking at these particle flows in detail.”

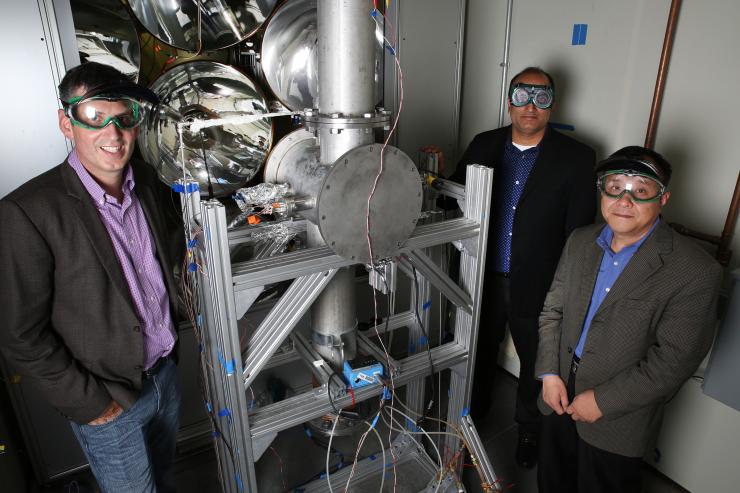

The work will include both theoretical and applied aspects, Loutzenhiser noted. “We will examine fundamental behavior of the particle flows and heat transfer for different solar particle heating receiver configurations. This work will then be used to support the design and development of real technologies at scale-up that are being pursued by other Generation 3 researchers within the scope of the program. The project will culminate in a suite of experiments that will use our high-flux solar simulator to closely mimic the conditions that the particle flows would experience under sunlight in an actual solar receiver.”

In addition to Yee, Loutzenhiser, Ranjan and Zhang, the overall DOE project will also include Said Abdel-Khalik and Sheldon Jeter, also mechanical engineering professors, who will support the development of the demonstration CSP facility proposed by Sandia National Laboratories. The proposed Sandia design will use particle heating technology. The team led by Abdel-Khalik and Jeter has been developing particle heating CSP technology in collaboration with Sandia and others for several years.

Ultimately one test facility will be built by a team to be chosen from among Sandia or competitors Brayton Energy and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Those three organizations received preliminary awards from the DOE.

The new DOE funding will extend previous research on high-temperature components, develop them into integrated assemblies, and test these components and systems through a wide range of operational conditions, the agency said.

If successful, the DOE expects that this will result in reducing the cost of a CSP system by approximately $0.02 per kilowatt-hour, which is 40 percent of the way to the 2030 cost goals of $0.05 per kilowatt-hour (kWh) for baseload CSP plants.

“DOE has led the world in CSP research,” said Daniel Simmons, principal deputy assistant secretary for the DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. “These projects will help facilitate the next wave of new technologies and continue the effort to maintain American leadership in this space.”

Through the Generation 3 CSP program, three teams will compete to build an integrated system that can efficiently receive solar heat and deliver it to a working fluid at a temperature greater than 700 degrees Celsius, while incorporating thermal energy storage, the agency said in its news release.

Over the first two-year period, those teams will work to de-risk various aspects of diversified CSP technology pathways, prepare a detailed design for a test facility, and be subjected to a rigorous review process to select a single awardee to construct their proposed facility. If selected, they will receive an additional $25 million over the subsequent three years to build a test facility that allows diverse teams of researchers, laboratories, developers and manufacturers to remove key technological risks for the next generation CSP technology, the DOE said.

Research News

Georgia Institute of Technology

177 North Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0181 USA

Media Relations Contact: John Toon (404-894-6986) (jtoon@gatech.edu).

Writer: John Toon

Georgia Tech is part of a new U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) initiative to develop the next generation of concentrated solar power (CSP). Shown in Georgia Tech’s high-flux solar simulator facility are Peter Loutzenhiser, Devesh Ranjan and Zhuomin Zhang. (Credit: Candler Hobbs, Georgia Tech)

John Toon

Research News

(404) 894-6986