Art and Technology Harmonize in School of Music

Shimon sings the evocative lyrics it composed in a voice that sounds more hypnotic than robotic. The mechanical “mouth” and “eyes” on the bobbing, rhythmic spheroid “head” give the machine an audience-friendly countenance, while its four automated arms glide across the marimba, playing the haunting melody.

A few blocks away at the Ferst Center for the Arts, an orchestra of 60-plus Georgia Tech students rehearse for their first performance of 2023. They’re practicing two newer works from modern composers, Anna Clyne and Stella Sung, and two classics, a Mozart symphony and a piano concerto from Edvard Grieg. The musicians are under the guidance of Chaowen Ting, director of orchestral studies at Georgia Tech.

They are seemingly divergent tableaus. The first, which could have been conjured from an Isaac Asimov novel, comes from the fertile mind of researcher and musician Gil Weinberg. The second is a traditional snapshot of human musicians playing their acoustic instruments together, the hive mind of focused, committed artists. But these are interwoven, equally essential scenes in the Georgia Tech School of Music story.

“It is almost mind-boggling, this continuum of creativity and technology — the breadth of research that our faculty and students are pursuing, the amount and quality of music being played on this campus,” said Jason Freeman, professor and chair of the School of Music.

Freeman, who plays saxophone and piano, earned his doctorate in composition, but also studied computer science and has always been interested in the intersection of music and technology. It’s what led him to Georgia Tech 18 years ago after graduate school.

“Here was a place where the people really understood both sides of who I was,” Freeman said. “They appreciated me as a musician, and I was thrilled about the incredible wealth of technological expertise — people who knew so much more than I did, who have become my collaborators.”

Chaowen Ting conducts the Georgia Tech Symphony Orchestra as it prepares for its first concert of 2023, February’s performance of Pivot, by Anna Clyne; Edvard Grieg’s Piano Concerto in A minor, Op 16; Stella Sung’s Game of Players, and a Mozart symphony.

“We’re training the next generation of scientists and engineers who will transform the ways we think about music, understand music, make music, and share music.” — Jason Freeman

There were no degree programs in music technology at the time, but planning for them was already underway, so Freeman and his colleagues were able to shape a truly interdisciplinary academic program. It allows students to bring their creative practice together with scientific research and engineering.

Today, students in the School of Music are earning bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in music technology. Basically, it’s become the kind of program Freeman and his peers would have appreciated when they were students.

“We’re training the next generation of scientists and engineers who will transform the ways we think about music, understand music, make music, and share music,” Freeman said. “In addition to music theory and history, our students are learning about music perception and cognition — how our brains process music.”

Students learn electrical engineering, signal processing, and computer science, as well as how computers analyze music through machine learning algorithms. They also take classes on generating music through deep learning composition algorithms.

“And they are connecting all of these dots to create a new vision for the future of music,” said Freeman.

The Future Is Now

(text and background only visible when logged in)

Every year in March, the future of music is on display, in front of an audience on the Georgia Tech campus with the Guthman Musical Instrument Competition. Musical inventors from around the world bring their innovative instruments to Atlanta — a suitable home for the event, as Georgia Tech’s Center for Music Technology has become world renowned for its musical innovation.

The winner in this year’s competition (March 10-11) and the $5,000 grand prize was the Zen Flute, a mouth theremin controlled by a performer’s waving hands. Developed by Wisconsin-based Muse Electronics, the instrument maps the pressure and shape of a performer’s mouth to determine the pitch output. The simplicity of use and the tubular shape are designed to increase the instrument’s accessibility.

Making music accessible is a big part of what drives Weinberg, co-founder of the Guthman competition and founding director of the Georgia Tech Center for Music Technology. For example, his lab famously developed a prosthetic arm that allows its user to achieve the necessary fine motor gestures to play piano. Ultrasonic sensors detect which prosthetic fingers the user wants to move. The Weinberg team also has created a prosthetic arm for drumming.

“Imagine Taylor Swift’s voice with the bass line from Michael Jackson’s ‘Beat It,’ with harmonies from Mozart and drums from somewhere else.” – Gil Weinberg

The lab’s other work under the accessibility umbrella includes a piano playing app designed to help in the rehab of stroke victims. Recently, Weinberg announced a new project designed to make creative mixing more accessible to a wider group of people: Mixboard allows anyone to drag, drop, and size any song into an interactive canvas, co-creating new musical landscapes.

“Imagine Taylor Swift’s voice with the bass line from Michael Jackson’s ‘Beat It,’ with harmonies from Mozart and drums from somewhere else,” said Weinberg, whose lab’s primary focus is robotic musicianship. The Center currently has several other research groups with a range of specialties, run by School of Music faculty: Music Informatics, directed by Alexander Lerch; Computational Music for All, directed by Freeman; and Computational and Cognitive Musicology, directed by Claire Arthur and Nat Condit-Schultz.

Human-Machine Collaboration

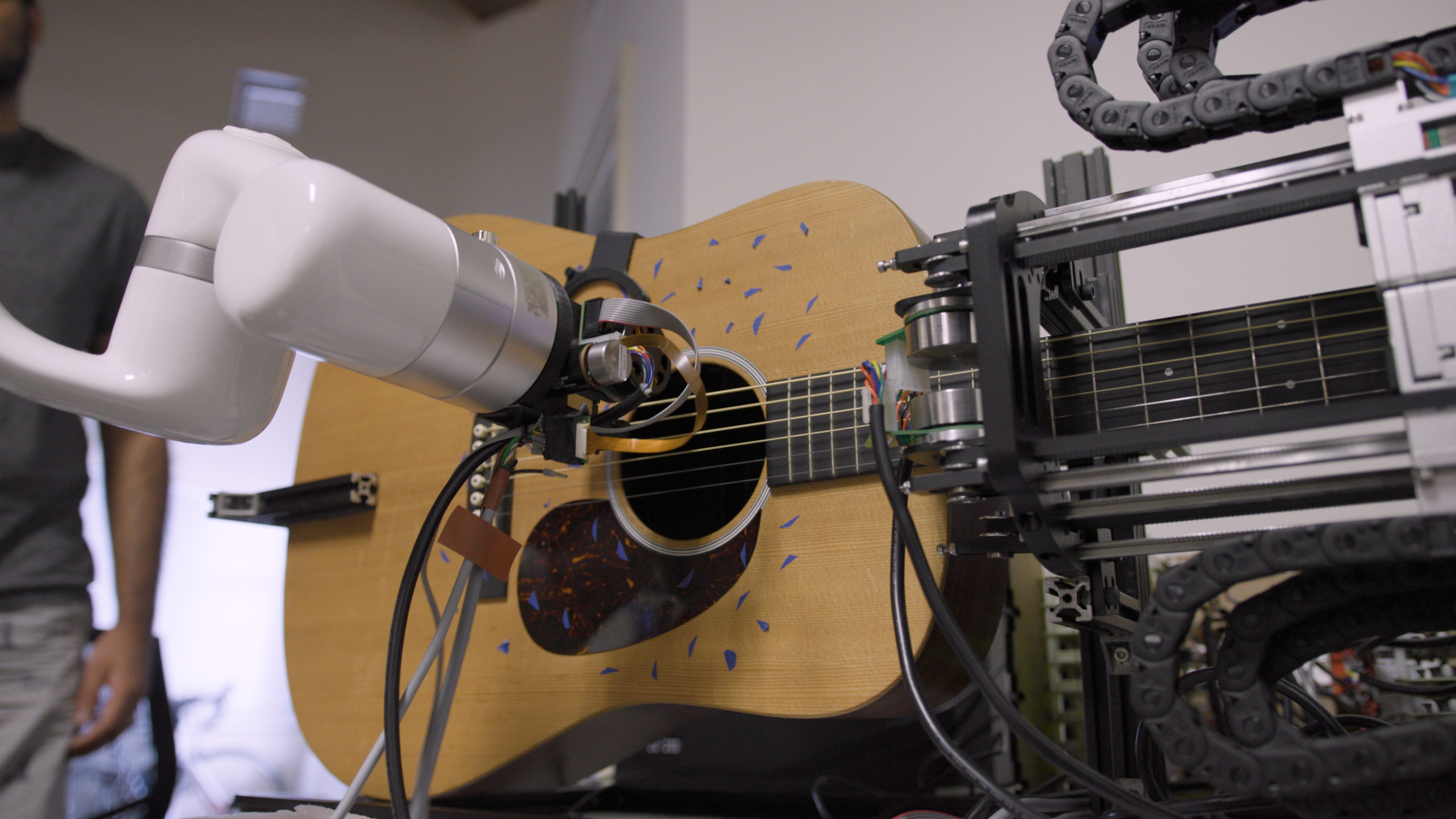

Shimon might be Georgia Tech’s most famous musical star. It’s performed on Jimmy Kimmel Live and jammed with Jeff Goldblum. It’s also the most well-known robot in the Weinberg lab, but there are other robotic musicians in the works, including one for guitar, one for violin, and something called Medusa.

Unlike the creature from Greek mythology, whose snaky locks could turn a man to stone, Medusa’s seven arms move rhythmically through its domed space, dancelike — similar to the robots the Weinberg team used in FOREST, a human-robot dance and music performance that was the result of a National Science Foundation-funded project aimed at enhancing trust between humans and robots. Medusa’s locks play string and percussion instruments, and they aren’t designed to be scary.

Shimon, the singing, marimba playing robot developed in the lab of Gil Weinberg, performs one of the songs that it co-wrote. The Weinberg lab has become a world leader in the creation of cutting edge musical robots and assistive technology.

Collaborations

The best music involves collaboration between artists, whose instruments are woven together seamlessly to create the songs we love. The same might be said of music technology research. The School of Music benefits from the culture of creative, interdisciplinary research at Georgia Tech. Here are the groups the School works with on a regular basis.

- The GVU Center

- Institute for People and Technology (IPAT)

- Center for Education Integrating Science, Mathematics, and Computing (CEISMC)

- Institute for Robotics and Intelligent Machines (IRIM)

- School of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE)

- George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering (ME)

- College of Computing

- Digital Media Program

- School of Psychology

- Center for Advanced Brain Imaging (CABI)

- Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering (BME)

- Invention Studio

- Georgia Tech Arts

“We want our robots to interact in a way that’s approachable, and music is a great medium for that,” said Amit Rogel, a graduate researcher on the Weinberg team, who explained that even Shimon, with its bobbing head, was designed to look more lifelike. “Music makes you move and makes you feel more alive. We want Shimon to reflect that.”

So, the researchers develop robots that can understand, improvise, and compose music, not to replace human musicians, but to work with them.

“The idea here is to come up with an entity that humans can collaborate with — that will inspire them to play music in new ways, and to think about music in new ways,” said Weinberg.

Chaowen Ting is fine with that. As an experienced symphony conductor who directs student orchestras at a leading research institute, she has a front-row seat to the ongoing procession (and progression) of musical technology in its various shapes and forms. She’s convinced that the research her colleagues and students are engaged in is overwhelmingly focused on supporting and expanding the creativity of human beings, not supplanting it.

“If you view humanities or art as only chasing perfection, then yes, we might be replaced by robots and machines someday,” she said. “But I don’t think achieving some idea of perfection is what music is about. It’s an artistic outlet that we use, as people, to express ourselves. A machine can’t replace that experience. But it can be a great tool, and it can help us understand music in ways we may not have imagined. The best technology has been serving the humanities for a very long time.”

Writer: Jerry Grillo

Multimedia: Christopher McKenney

Media Contact: Jerry Grillo | jerry.grillo@ibb.gatech.edu