Reframing Antarctica’s Meltwater Pond Dangers to Ice Shelves and Sea Level

Oct 29, 2019 — Atlanta, GA

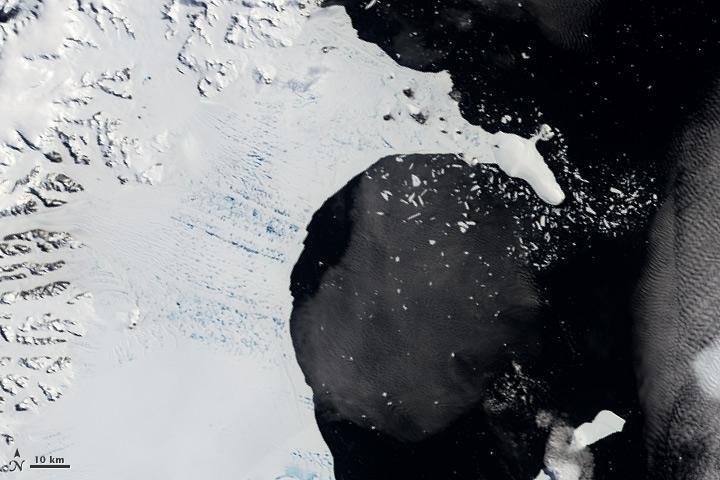

Before its sudden shattering, numerous meltwater ponds riddled Antarctic ice shelf Larsen B. They are seen in this 2002 satellite image as a matrix of aquamarine spots. Scientists believe that the ponds hydrofractured the kilometer-thick ice shelf, causing its swift destruction. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

Dangers to ancient Antarctic ice portend a future of rapidly rising seas, but a new study may relieve one nagging fear: that ponds of meltwater fracturing the ice below them could cause protracted chain reactions that unexpectedly collapse floating ice shelves. Though pooled meltwater does fracture ice, ensuing chain reactions appear short-ranged.

Still, massive increases in surface melting due to unusually warm weather can trigger catastrophic ice shelf collapses like that of the iconic shelf “Larsen B,” which shattered in 2002. Now, a study led by a researcher at the Georgia Institute of Technology has modeled fracture chain reactions and how much water it would take for a repeat of that rare, epic collapse.

Larsen B’s disintegration was preceded by an atypical heatwave that riddled it with meltwater ponds, focusing researchers’ attention on pond fracturing, also called hydrofracturing. They discovered that a melt pond hydrofracturing the ice shelf can prompt neighboring ponds to do the same. Concerns grew of possible extensive chain reactions, which the new study addressed.

Too much meltwater

“The chain reactions will not spread that far on the ice shelf,” said Alex Robel, an assistant professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. “Normally, it would take many years for the chain reactions to have an effect on the integrity of the ice shelves. But there’s a caveat. Ponds that are close together and growing rapidly deeper could destroy the ice’s integrity.”

“There is a speed limit in the study that shows that an ice shelf can’t collapse ridiculously fast,” said co-author Alison Banwell, a glaciology researcher at the University of Colorado Boulder. “However, if it becomes as covered in meltwater ponds very quickly like Larsen B was, it can collapse in a similar way.” She added, “Multiple hydrofracture chains originating in different areas of an ice shelf could also lead to a larger-scale ice shelf breakup.”

The researchers published their results in the journal Geophysical Research Letters on October 24, 2019. The research was funded by the National Science Foundation and the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at CU Boulder. An unrelated, recent study reported a record number of meltwater ponds on Antarctica.

“Currently there are not nearly enough ponds on any ice shelf for a repeat of Larsen B, but much meltwater is weighing on ice shelves and contributing damage to them,” said Banwell, who helped pioneer hydrofracture research on ice shelves.

Q&A

Broken ice shelves themselves don’t add much to sea level. So, why care?

Ice shelves float in the ocean, where they already contribute to sea level, so when they break up or melt, they don’t add much more to it. But many ice shelves push back against glaciers on land that do drive up sea level when they enter the ocean.

With the shelf gone, the speed of glacial flow can jump four- to tenfold. Glaciologists were not aware of this until Larsen B, which was a kilometer (0.62 miles) thick with a surface of 3,250 square km (1,250 square miles), splintered within weeks, and glacial flow behind it surged.

“Our research field thought ice shelves weren’t too important, then Larsen B showed us that was incorrect. Buttressing by ice shelves really is the thing that stabilizes the glaciers. Few issues are more significant than those that this study addresses,” said Brent Minchew, an assistant professor of geophysics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Minchew was not involved in the study but recently co-published another study that relates to it. The MIT study rules out one absolutely nightmarish scenario of rapid glacier fracture due to the disappearance of ice shelves. But he and the other researchers reiterated that glacial flow nonetheless speeds up strikingly when ice shelves disappear.

Also, most Antarctic ice shelves probably formed in the last ice age, and it could take another ice age to replace them.

[Ready for graduate school? Here's how to apply to Georgia Tech.]

How does hydrofracturing work, and how did the study model its effects?

When meltwater ponds on top of cracks in the ice grow heavy, they can hydrofracture the ice.

“The water pressure concentrates down to a point called a crack tip. It tries to push the crack apart and make it deeper, and the ice pushes back. When the water gets deep enough, it can win out and propagate the crack to the bottom of the ice shelf,” Robel said.

The water drains down the crack, into the ocean, then the ice hops back up, making new cracks that can trigger neighboring ponds to hydrofracture, too. The study showed that this would encompass only small numbers of ponds.

Conveniently for Robel, who explores ice dynamics with math, physics, and computer science, as ice shelves form, regimented matrices of surface dents appear in them, and that’s where the ponds collect.

Robel could apply computer science modeling called cellular automata – known from pixelated matrix-like video games – to model hydrofracture chain reactions. The model even outputs animations that the researchers named “minesweeper plots” after the classic 1990s computer game.

Does the study mean there is less danger than before of glacial flow accelerating?

No, the study simply adds to scientific knowledge, and actually, the flow of some glaciers on Antarctica has already sped up a lot.

“Maybe this mechanism is not something we have to worry as much about. But we shouldn’t breathe a sigh of relief because there are plenty of other ways of getting a whole lot of ice out of West Antarctica quickly,” Minchew said.

Perhaps the greatest potential for glacier loss is instability where glaciers rest on the ground next to seawater. A study Robel published in July projected that instability to be extremely likely to accelerate sea level rise.

How does this study help advance glacier research?

It makes it easier to look for harbingers of ice shelf damage.

“Looking at the volume of water on the surface of the ice is much easier than looking for stress failures within the ice,” said Banwell, who will visit Antarctica in November to study melt ponds on the George IV ice shelf.

Also READ: Instability in Antarctic Ice Projected to Make Sea Level Rise Rapidly

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation (grants NSF PLR-1735715 and NSF PLR-1841607) and by the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at CU Boulder. Any findings, conclusions or recommendations are those of the authors and not necessarily of the funding agencies.

Writer & Media Representative: Ben Brumfield (404-272-2780)

Email: ben.brumfield@comm.gatech.edu

Georgia Institute of Technology

177 North Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0181 USA

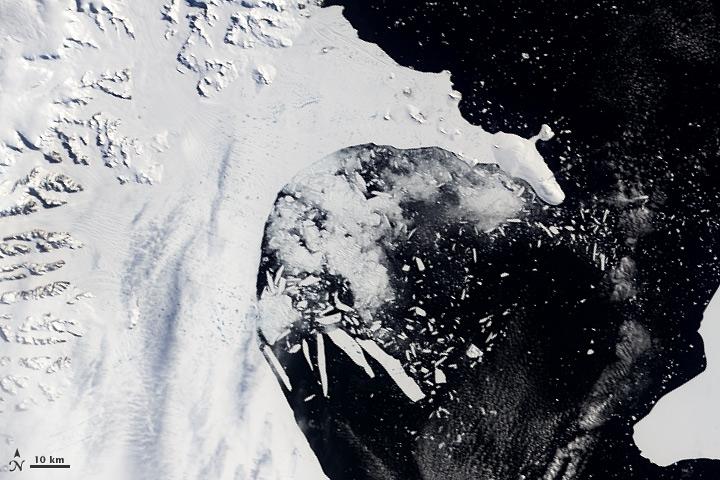

Antarctic ice shelf Larsen B suddenly broke apart in 2002 after an anomalous heatwave. The shelf may have formed 10,000 years ago but shattered in just two to three weeks' time. After its disappearance, the glacier behind it sped up its flow toward the ocean, pushing up sea level faster than it otherwise would have. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

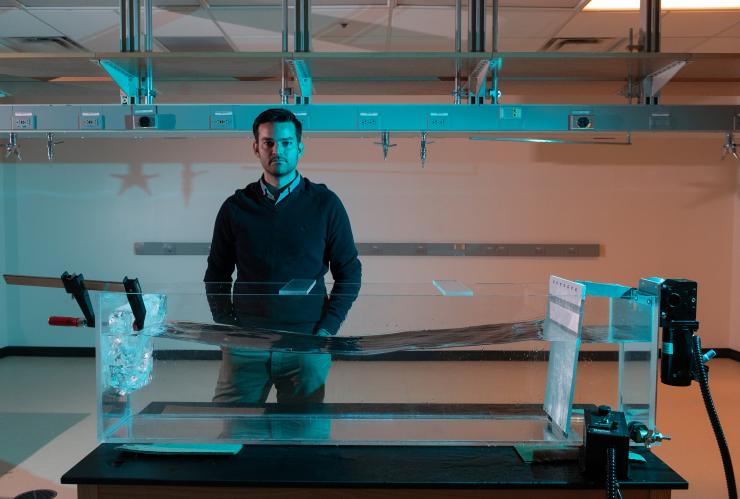

The study's principal investigator Alex Robel in his lab at Georgia Tech standing at an ice-melting tank. Credit: Georgia Tech / Allison Carter

Co-author Alison Banwell wades through a meltwater pond in Antarctica. Banwell has helped pioneer research into ice shelf hydrofracturing dynamics. Credit: Banwell / press handout via UC Boulder

The study's principal investigator Alex Robel observes ice fracture patterns caused by wavy water in a test tank at his lab at Georgia Tech. Credit: Georgia Tech / Allison Carter

Principal investigator Alex Robel holds up ice that has been reduced by contact with water, revealing patterns of ice destruction. Credit: Georgia Tech / Allison Carter