Small Things Considered at Suddath Symposium

Feb 04, 2018 — Atlanta, GA

The 2018 Suddath Symposium packed the room for every session.

There are vast, invisible, churning communities of organisms living all around and inside every living thing on Earth, overwhelmingly outnumbering us. We can’t see them, but their influence is profound – their processes can connect us, sustain us, protect us, or destroy us.

They are the bacteria, fungi, viruses and other microbes that comprise the world’s many microbiomes, which were the focus of this year’s Suddath Symposium (Jan. 30-31) at the Petit Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

“A microbiome is, generally, the collection of interacting microbes in a particular location, and the locations vary in scale,” said Brian Hammer, associate professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Biological Sciences and a Petit Institute researcher.

Hammer and Frank Stewart, also a Petit Institute researcher, were co-chairs of what may have been the best-attended Suddath Symposium in the event’s 26-year history. Every session, for all 12 speakers, featured standing-room crowds in the Suddath Room, in addition to people watching the simulcast in the Petit Institute atrium, and across campus – symposium seating was sold out before the early registration deadline, in early January.

It was an opportunity to showcase work being done at Georgia Tech and across the country and the attendance reflected growing and diverse interest in microbial science.

“Over the last five years or so, the importance of and interest in microbial science at Georgia Tech has really increased,” said Stewart, associate professor in the School of Biological Sciences. “We’ve added faculty, resources, the field is growing. All of those things are coming together right now.”

Microbes Are Popular

The topic of microbiomes has infiltrated public consciousness – this is a popular subject, Hammer said. “You’ll see microbiome research in high profile journals every week now, it’s one of those things that’s made it into the mainstream. You go home and your parents are starting to ask about these things. Everybody seems to care about their microbiomes, and we’re all trying to figure out how these things work, and we’re right at the forefront here at Tech.”

The interest, like the science, is deep and wide. For instance, there’s a lot of research into the microbiomes of the human gut and lungs, much of it fueled by initiatives like the ongoing NIH Human Microbiome Project. Meanwhile, there’s the Earth Microbiome Project, across ecologies and habitats and environments.

“There are so many scales, some more narrowly focused, some broader, and we tried to reflect that range of interest in this symposium,” Hammer said.

The symposium, which was entitled, “The Chemical Ecology of Microbiome Interactions,” presented research unified by the goal of understanding microbe-microbe and microbe-host interactions, spanning diverse specialties, including biomedicine and genomics, chemical ecology, biogeochemical cycling, environmental science, biophysics, and the evolution of microbial interactions, including those involving pathogens.

Two Days of Brain Candy

Accordingly, the symposium drew speakers who are among the nation’s thought leaders in both environmental and human microbiome research (including several from Georgia Tech), presenting their research over, “two days of brain candy,” which is how Bonnie Bassler of Princeton University described the gathering.

“It was a thrill,” said Bassler. “There was such a diverse range of science discussed, and every speaker still made sure that everyone understood their talks, which is remarkable when you consider the range of topics.”

As tradition demands, the two-day symposium began with a research presentation from the grad student who was named the Suddath Award winner during the Petit Institute holiday party back in December. These presentations often have little connection with the symposium theme. This year, David Hanna, a doctoral candidate in the lab of Petit Institute researcher Amit Reddi, presented his research, entitled, “Shedding Light on Heme Signaling Networks with Heme Sensors and Quantitative Mass Spectrometry.”

Then it was all about the many interactions of very tiny things, the contact and communication between microbes. Bassler, who was Hammer’s postdoctoral advisor, led off the microbiome presentations on Tuesday with a talk entitled, "Bacterial Quorum Sensing and its Control."

Bassler is a wet lab microbiologist, said Hammer, and she was followed by a who’s who list of microbial researchers from beyond the Georgia Tech campus. On Tuesday, Jon Clardy, a chemical biologist from Harvard University, spoke on, “Microbiomes, Chemical Ecology, and Animal Development.” Seth Bordenstein, a classically trained evolutionary biologist from Vanderbilt University, delivered a presentation that asked, “How do Microbes Form Relationships With Animals?”

Tuesday’s sessions ended with a presentation from Mary Voytek, a microbiologist who heads up NASA’s Astrobiology Program, that really took the subject to far out places – like, deep onto our solar system, to the moons of Jupiter and Saturn and the search for life beyond Earth, with a talk entitled, “How can Microbiomes Serve as a Model for the Emergence and Early Evolution of Life.”

“Mary is very interested in how microbial systems that we can study on Earth might inform our understanding of how life might look on other planets,” said Stewart.

Mary Ann Moran from the University of Georgia led off Wednesday with her talk, “Chemical Currencies of the Ocean Microbiome,” followed by Tim Read from the Emory School of Medicine, and his presentation, “Pathogen Genomic Variation in the Context of a Human Microbiome.”

Rebecca Vega Thurber from Oregon State University who has focused much of her research on coral systems in the oceans, delivered a presentation entitled, “The Roles of Environmental Nitrogen in Coral Microbiome Dysbiosis and Disease.”

Karine Gibbs, the second speaker from Harvard and the final presenter from outside Georgia Tech, stressed the importance of contact-dependent interactions in her talk, “Know Thy Neighbors: The Influences of Self/Non-Self Recognition on the Collective Migration of a Bacterial Population.”

Gibbs, said Hammer, “was one of the pioneers that figured out bacteria have ways to discriminate self from non-self, and use that information to organize microbial communities.”

Civics at the microscale? No, not quite. But Gibbs, who has observed wholesale warfare between microbial armies, is working with her lab to develop models that clarify the differences between lethal and non-lethal contact dependent interactions. “The predominant theory in microbiology is that all of these interactions would be about death,” Gibbs said. “Our evidence shows that’s not the case.”

Tech Researchers Take Stage

A quartet of Georgia Tech researchers also took research center stage – or, center projection screen – during the two-day symposium.

Neha Garg, assistant professor in the School of Chemistry and Biochemistry, gave a talk on Tuesday entitled, “Chemical Chatter between the Cystic Fibrosis-associated Microbiome.” She’s one of the new microbiology-focused faculty members at Georgia Tech, arriving last year following her postdoctoral work at the University of California-San Diego.

“She’s studying the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis, trying to understand the nature of the chemical compounds that organisms use to interact with other micro-organisms, or a host,” Hammer said.

While most researchers engaged in this area would typically remove the organisms that cause a bacterial infection in a cystic fibrosis patient, and study them in a petri dish, Garg has developed a method to study all of the bacterial chemicals in an infected lung, based on their DNA.

“She’s doing it spatially, building a three-dimensional map of the infected lung,” Hammer said. “She’s taking the research to the next level.”

The other three Georgia Tech researchers were part of the Wednesday lineup.

Joel Kostka, professor and associate chair of research in the School of Biological Sciences, delivered a talk called, “The Sphagnum Phytobiome: Ecosystem Engineers of the Global Carbon Cycle.”

“Joel is one of the leaders in thinking about microbes in real world environmental settings, which are often quite diverse,” Stewart said. “He studies systems ranging from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic. He combines a wide range of approaches in thinking about the system holistically.”

Petit Institute researcher James Gumbart, from the School of Physics, talked about, “Molecular Mechanisms of Nutrient Acquisition and Virulence Revealed by Molecular Dynamics Simulations.”

Gumbart is one of that breed of physicist who calls himself a ‘squishy,’ according to Hammer. “They work in ‘squishy physics.’ His expertise is in using mathematical simulations to look at these molecular machines that bacteria use to interact with one another,” Hammer said.

The last speaker of the symposium was Marvin Whiteley, a professor in the School of Biology and the Emory School of Medicine, whose talk was entitled, “Biogeography of in vivo Biofilms.”

Like Hammer, Whiteley was trained as a classical bacterial geneticist, “which is, you take an organism and dissect it at the level of DNA to figure out how it’s capable of accomplishing certain tasks,” Hammer said. “Marvin has transitioned in the last 10 to 15 years to focusing on the organism that causes disease in cystic fibrosis patients.”

At some point, Whiteley’s work in cystic fibrosis as a geneticist would ideally dovetail with Garg’s work in the same disease as a chemist. That isn’t by accident.

“That’s an example of complementary expertise that Georgia Tech is bringing together,” Hammer said. And it gets to the heart of the reason for this topic at this symposium at this time. “We’ve reached a stage now where these interactions are allowing us to move the science forward in ways we weren’t able to at Georgia Tech until fairly recently. We think we’re at a turning point.”

Microbiology, the study of the smallest living organisms, is playing an increasingly expanded role in the further understanding of life, and how it evolves, thrives, or doesn’t. As she left to catch a plane back to Boston, Gibbs thought about the two days of multifaceted brain candy, and its impact on her.

“This was an amazing community of science,” she said. “The breadth of it! This was a nice reflection of the dynamics that are in place right now in microbiology, and I think it helped illustrate how microbes, whether we like it or not, are integral to so many aspects of our lives and our living planet.”

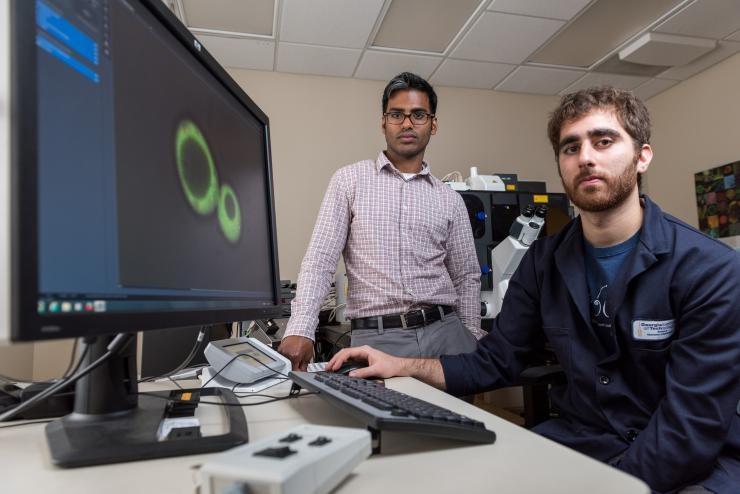

Suddath Award Winner David Hanna (right) with his Ph.D. advisor Amit Reddi

Frank Stewart and Brian Hammer

Petit Institute researcher Will Ratfliff raises his hand to ask a question of fellow Petit Institute researcher Marvin Whiteley during the last presentation of the 2018 Suddath Symposium.

Bonnie Bassler of Princeton University

Karine Gibbs of Harvard and Symposium co-chair Brian Hammer enjoy a post-presentation laugh.

Jerry Grillo

Communications Officer II

Parker H. Petit Institute for

Bioengineering and Bioscience