Urine Test to Evaluate Immunotherapy Success Gets $1.8 Million NIH Research Grant

Apr 02, 2019 — Atlanta, GA

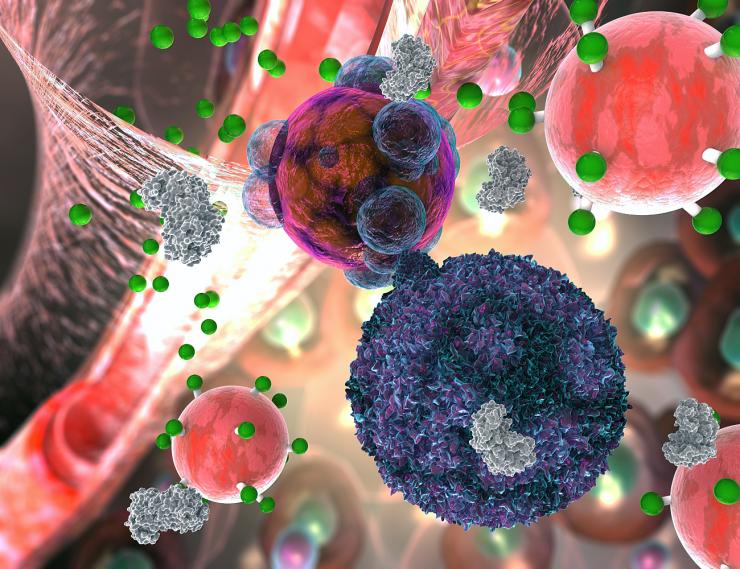

A T cell, here in violet, makes contact with a transplant organ cell, here in brown and purple. The T cell secretes the enzyme granzyme B, here in gray, which attacks the organ cell. But granzyme B also severs fluorescent signal molecules, in green, from the rejection detecting nanoparticle, in light red. The signal molecules makes their way into the urine, where they give off a fluorescent cue.

New immunotherapies can dramatically defeat cancer. But more often, cancer evades them, and doctors need to know quickly when that happens, so they can adjust treatment. An experimental urine test to detect immunotherapy effectiveness very early has received a major funding boost.

The National Institutes of Health has granted $1.8 million to a research project at the Georgia Institute of Technology, where the lab of Gabe Kwong has already established a platform to detect complex disease and immune activity. Kwong will use the new funding from the NIH’s National Cancer Institute to advance the platform to evaluate immunotherapy progress.

The platform uses an intravenous injection of “activity sensors,” nanoparticles that detect early enzyme activity of immune cells attacking cancer. The sensor confirms the attack with a fluorescent signal in the urine.

Shifty resistance

Cancer’s defenses are crafty and can thwart treatment from the start or disrupt initially successful treatment later on, so progress must be continually monitored, which Kwong’s lab is engineering the particle to do. Early resistance to therapy looks very different from later resistance.

“We need to be able to classify different forms of resistance, so we can combat them better,” said Kwong, an assistant professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University.

He plans to adapt the sensing technology to profile those subtleties. It is already engineered to have advantages over other tests that have recently entered the market, which look for signals that come later, such as dead cancer cells shedding their DNA into the bloodstream.

“These tests can be quite effective, but some issues limit them, particularly in early detection: You have five liters of blood. Whatever the cells shed gets diluted significantly in your bloodstream,” Kwong said.

That makes these signals harder to detect in blood tests.

Enriched signals

“Our sensors’ signals get concentrated in the urine, so, not only are they not diluted in the blood, but we usually see a hundred- to thousandfold signal enrichment.”

Kwong’s lab has already developed the sensors, which are biocompatible nanoparticles, refined them as a reliable platform, and engineered variations that experimentally sense blood clots, liver fibrosis, organ transplant rejection, and cancer. Kwong has published multiple papers on activity sensor urine test successes.

Kwong’s endgame ambitions: “In five to ten years, we want to expand the platform to detect most all major complex diseases and progress in treating them.”

Q & A

What is the activity sensor and how does the urine test work?

The sensors are nanoscale balls with bristles made of short amino acid strands that have fluorescent “reporter” molecules attached to their tips. The sensors tend to accumulate in compromised tissue like cancer.

When immunotherapy -- which can be engineered T cells or the body’s own T cells aided by medication -- attack cancer cells, the T cells secrete an enzyme called granzyme that severs target amino acid strands in the cancer cells, triggering their death. The activity sensor’s bristles mimic those strands, so granzymes cut the bristles at the same time.

“That releases the reporter molecules, which are so small that they easily make it through the kidney’s filtration and go into the urine,” said Kwong who directs the Laboratory for Synthetic Immunity in the Coulter Department.

Then the urine turns a fluorescent color that can be analyzed to determine the intensity of the immunotherapy’s attack on cancer.

[Thinking about grad school? Here's how to apply to Georgia Tech.]

Is there a need for this kind of test?

“Many patients, especially those with solid tumors, are not responding to this treatment,” Kwong said. “The non-responders need to be detected very quickly.”

There are also diagnostic pitfalls the experimental sensor is devised to overcome: For example, a current measure of treatment success is tumor shrinkage, but when T cells initially cram into a tumor, it can swell. That sometimes leads doctors to believe that a therapy that is actually very effective is not working, and they may discontinue it.

“This test does not measure size; it measures activity,” Kwong. “If those swelling tumors are very high in granzyme activity, that’s a great sign, and we will be able to pick that up.”

How is the dream of detecting most known complex diseases even feasible?

Quite conveniently, the human genome produces “only” 550 proteases, a particular type of enzyme relevant to detecting and combating disease. Kwong believes researchers can adapt this platform to detect any of them and that there’s a need for that.

“Granzymes are also activated by other things like an infection, so detecting granzyme alone risks getting interference when you’re looking at cancer treatment effectiveness. We’re developing a panel of sensors that gives us the specificity of T cell activity in tumors over the possible activity of T cells fighting, say, a cold,” Kwong said.

“We want to build 550 different protease-detecting probes, and depending on what disease you have, they would expose a profile of the proteases in varying ratios.”

The probes could be combined into a cocktail to detect budding cancer, immunotherapy effectiveness or infections, and machine learning would analyze their respective fingerprints in the urine signals.

Also READ: Mending a Broken Heart - 6 cardiac solutions currently in testing

The grant was provided by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health. The grant number is 1 R01 CA237210-01. The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Media relations assistance / writer: Ben Brumfield

(404) 660-1408

Research News

Georgia Institute of Technology

177 North Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0181 USA

The activity sensor illustrated in reddish-pink with small, green attachments is shown here in its application to detect organ transplant rejection. T cells secrete the enzyme granzyme, here in gray, which kills cells but also severs the fluorescent green signal molecules from the activity sensing nanoparticle. The green signal molecules make their way into the urine, where they give off a fluorescent cue. Credit: Georgia Tech / EllaMaru Studios work for hire / press handout

Georgia Tech and Coulter Department researcher Gabe Kwong (r.) next to a liquid nitrogen storage vat in his lab. Credit: Georgia Tech / Allison Carter